Roam the internet’s endless pages on writing tips, online writing best practices, and search engine optimisation how-tos and you’ll find a common directive: Avoid the passive voice.

Of course, the internet doesn’t hold a monopoly on Avoid Passive (to borrow a term from Stanford linguist Arnold Zwicky). We’ve been told to create active sentences and phrases for a long time. But where does this wisdom come from and why does it hold such validity today?

In today’s post, we’re going to turn back time and look at the history of Avoid Passive before turning our attention to today’s passive aggressors.

And in next month’s post, we’ll examine what the passive voice is (there seems to be a lot of confusion), how it operates, and why it’s the better choice in some circumstances.

Where Did Avoid Passive Come From?

In 1947, Orwell instructed readers in his much-anthologized essay ‘Politics and the English Language’ to: “Never use the passive where you can use the active.”

However, there are plenty of passive constructions in the essay. According to Geoffrey Pullman, at the University of Edinburgh, 26 per cent of the transitive verbs Orwell uses are in the passive. A much higher percentage than the 13 per cent in most prose.

But Avoid Passive goes back a little further than ‘47. Zwicky notes that neither Hall (1917) nor Fowler (1926) take issue with the passive in their influential grammars but from the 30s onward, grammar handbooks start to demonize the passive as weak and ineffectual.

Then, Strunk and White came along with has been wonderfully called a “vile little compendium of tripe about style.”

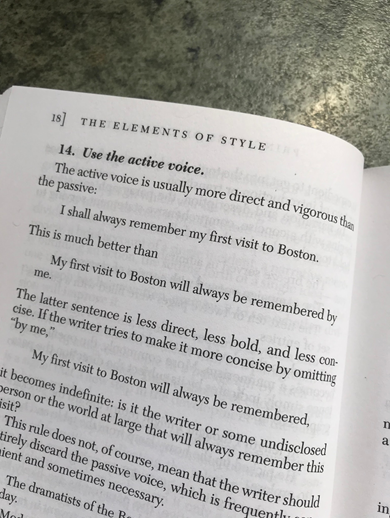

The Elements of Style was first written by William Strunk Jr. as a writing aid for his students. Later, E.B. White (of Charlotte’s Web and The New Yorker fame) added to the guide and in 1959 it was published by Macmillan with substantial additions from both authors.

Elements has held tremendous cultural sway ever since. Time even named it one of the most influential books written in English since 1939.

Unfortunately, Strunk and White advise against the passive whilst simultaneously utilising passive clauses:

“Many a tame sentence of description or exposition can be made lively and emphatic by substituting a transitive in the active voice for some such perfunctory expression as there is or could be heard.”

Nonetheless, this hypocrisy largely passed without scrutiny and Avoid Passive began to form a key role in the modern ideology of English style.

Today’s prescriptivists come in two forms: human and app. While grammar curmudgeons still publish high-blown works mostly informed by personal preferences, apps govern much of the writing you encounter online.

Not so Apt Apps

Content is king online. Words are used to sell and to deliberately court the good graces of search engines. Systems exist to ensure much of the writing you see is fine-tuned to suit the digital environment.

Content writers type, editors adjust, and apps dictate style. Whether it’s a limit of 20 words per sentence, too many adverbs, or too much passive voice, there’s an app to attack text and homogenise style.

The one I loathe is Hemingway, which promises to make your writing “bold and clear.” Hemingway, named after the famously terse writer, grades text against an opaque set of requirements. It hates long sentences, subordinate clauses, big words such as “utilise,” adverbs, and the passive voice.

Hemingway is not always consistent and misses some passive constructions while flagging others that are arguably not passive at all. Take a read of this fun New Yorker essay to see how the man himself fared on the Hemingway test.

But Hemingway isn’t alone here. Yoast, a popular SEO WordPress plugin, has similar requirements.

Upholding the Passive Hatred

Of course, these apps didn’t decide by themselves which elements of style were good and which were no-gos, they were programmed by people upholding what they’ve been taught. Hating on passive constructions is now part of the good writing cultural wallpaper.

Perhaps the most annoying thing about all the passive derision is that many people who tell writers and editors to avoid the passive have absolutely no idea what it is or how it operates. Or worse, think it has something to do with passivity — it doesn’t.

There also seems to be a shift occurring whereby the passive voice as a term is beginning to mean any statement that appears shifty or evasive. No matter what the grammatical construction is.

To illustrate this, Berkeley linguist Geoffrey Nunberg points to various articles, including one from CNN, where writers chastise politicians for disingenuous statements and call these statements passive constructions. In fact, none are passive in the grammatical sense.

Language change occurs, meanings shift. That’s normal in a living language. What will be interesting to watch is whether this new use of the term, with its sneaky connotations, will further drive the Avoid Passive dictate.

Next month, why we need the passive voice and how it works.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed