…It is a simple truth that in most sentences you should express action through verbs, just as you do when you speak. Yet in so many sentences the verbs are smothered, all their vitality trapped beneath heavy noun phrases based on the verbs themselves. There is nothing wrong with nominalization as such – it is a useful part of the language. But overusing it tends to freeze-frame the action…. (Cutts, 1996)

This is the final post in my summer series on machine translation (in September my guest writers will be returning with lots of interesting topics), and I’d like to briefly look at nominalizations. Basically, a nominalization is a verb converted into a noun. The fun usually starts when it needs support from another verb, such as in the phrase “to give consideration to” (where “give” helps out) meaning the same as “to consider something”.

He is interested in obtaining a quotation for…

He expressed his interest in obtaining a quotation for…

Business and science tend to have a penchant for indirectness, verblessness and personification:

Die Schnelligkeit der Rückantwort und die Bereitstellung der Antworten

[The speed of reply and the provision of answers]

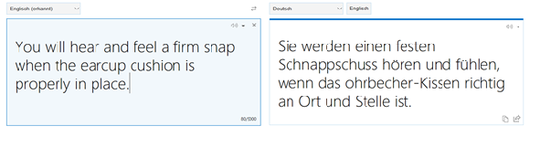

Cleaning and user maintenance should not be made [carried out] by children unless they are older than 8 years and supervised.

Psycholinguistic studies have found that nominalizations seem to pose greater processing demands than individual sentences containing verbs, mainly because the results of nominalizations tend to be complex multi-clause sentences.

My going to the store afterwards led to Sam’s objecting most vigorously.

The sheriff pursued the cattle-rustling cowboys.

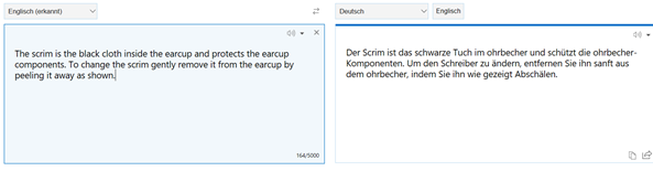

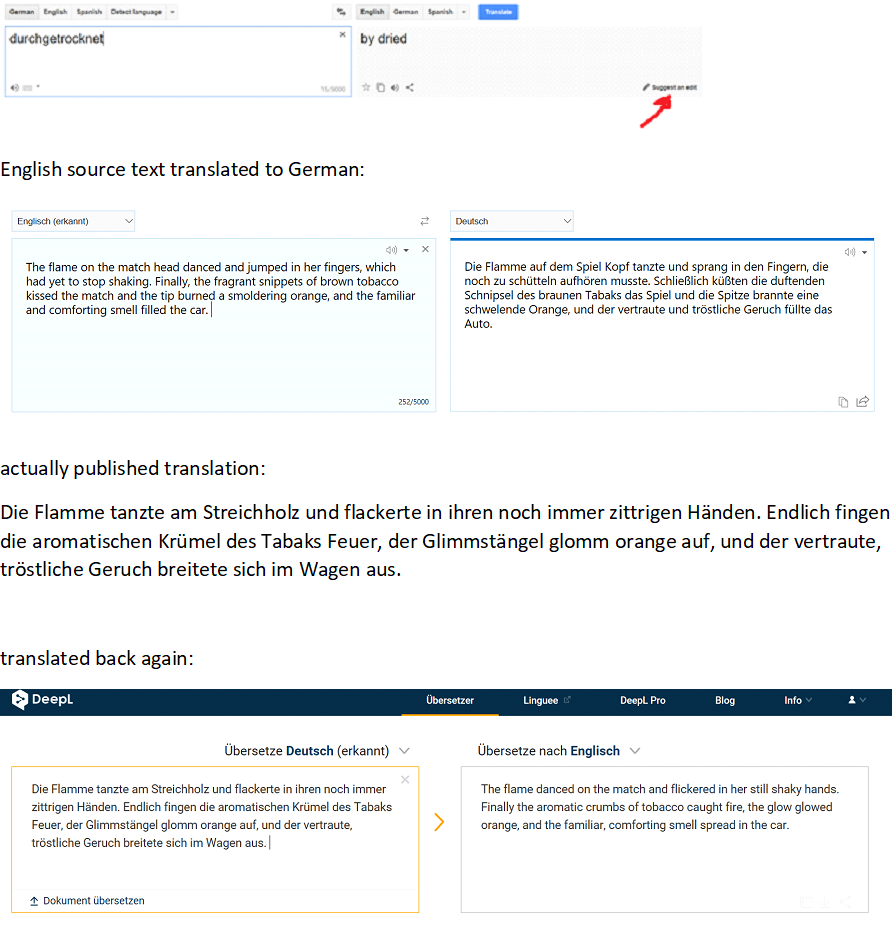

So, let’s release the vitality of verbs trapped beneath heavy noun phrases and see what the free online translation programs think. “No small part of language’s value lies in its flexibility” (Quirk & Greenbaum) after all, so there should be scope for remediation.

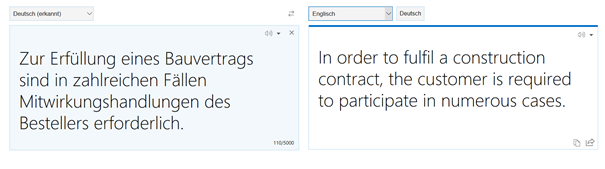

Zur Erfüllung eines Bauvertrags sind in zahlreichen Fällen Mitwirkungshandlungen des Bestellers erforderlich.

A literal translation could be:

The fulfilling of a construction contract in many cases necessitates participatory action by the customer.

Not very nice, is it? Or (with a different focus):

In many cases, the customer’s participation is necessary for the fulfilling of a construction contract.

Or even less literal, less formal translations, depending on the context. We don’t really need to be so literal unless it’s a legal text. But I think the machine also felt that the nominalizations sounded a bit odd in English:

It gives us “in order to fulfil” and “the customer is required to participate”. Interesting. Not a nominalization in sight! And if we hand the translated sentence back and ask it to translate it into German, we get:

Um einen Bauvertrag zu erfüllen, ist der Kunde verpflichtet, sich in zahlreichen Fällen zu beteiligen.

The meaning has changed slightly, but still there are no nominalizations. Thank goodness.

Writing well and writing for an international audience are two sides of the same coin. Get the one right and chances are you (and your machine translation tool) will succeed in getting your message across no matter what language you are writing in. Make sure you avoid the pitfalls I talked about in this series on machine translation, such as when using punctuation, the active and the passive voice, literal translations and special vocabularies, homonymy and misspellings, and you’ll capture your audience (and save time and money to boot).

Good luck! And have a great summer!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed