The best advice for budding writers and translator I’ve come across is that you should go over your text with fresh eyes and ruthlessly cut out anything you feel is redundant or superfluous. For me, it’s often cut, cut, cut, with my grey cells screaming, ‘You want to get rid of WHAT?! You CANNOT be SERIOUS!’ So, when I write in this blog I tend to just let loose and give in to the inspiration of the moment without regard to good writing practice. I hope you will forgive me. And I hope you’ll find something interesting to read. Continuing in the series on machine translation this week, I would like to talk to you about two interesting things I’ve noticed coming up time and again. First, let’s look at the passive voice.

You can make writing clearer by using verbs in the active voice and avoiding the passive. For instance, if you want to make it clear who is doing (or supposed to be doing) an action:

Make sure you update your virus protection programs regularly.

Do not continue to press the On/Off switch after the machine has been automatically switched off.

Before you can claim your tax refund, you will need to verify your identity.

This is a sensible precaution when conveying vital information. Passive voice verbs can keep readers guessing as to who is doing what if no ‘agent’ (or ‘doer’) is mentioned. Consider the following sentences:

It must be insured that the virus protection programs are updated as quickly as possible on all computers when a new virus is detected.

Appropriate measures must be prepared and tested.

Do you know who is doing the action? Do you know who is supposed to be doing it? (Could be you.) What about the following example?

If the cable is damaged or cut during work, do not touch the cable.

It seems we don’t have to know. This is because sometimes the context makes it irrelevant as to who is doing the action conveyed by the verb. For example:

Do not continue to press the On/Off switch after the machine has been automatically switched off.

You don’t need do know who did the switching off, the machine itself or maybe some external electronic system.

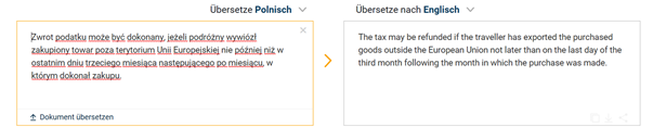

Let’s now look at a different example and ask the computer to do some translating for us.

The tax may be refunded if the traveller has exported the purchased goods outside the European Union not later than on the last day of the third month following the month in which the purchase was made.

The English sentence contains two passive voice verbs (‘refunded’ and ‘made’) and a verb in the active voice (‘exported’) plus an agent given as ‘the traveller’.

The tax may be refunded if the traveller has exported the purchased goods outside the European Union not later than….

The traveller is clearly doing the exporting. What about the ‘refunding’? Do we need to know who is doing it? No, but we are told something about the restrictions that apply:

…if the traveller has exported the purchased goods…not later than on the last day of the third month in which the purchase was made.

Again, the passive ‘was made’ does not tell us anything about the agent of the action – it could be ‘the traveller’ or somebody else –, but we do know that it was a ‘purchase’ that was made.

And now let’s put the machine to the test with a sentence that isn’t formed quite so well. The following English sentence came up in a text recently:

A tax refund can be made if the traveler purchased goods exported outside the EU no later than the last day of the third month following the month in which the purchase was made.

As you can clearly see, there has been a mix-up and the sentence no longer makes sense. A human being will recognise this error and rephrase the sentence accordingly because he or she understands the meaning. The machine, by contrast, takes the clauses provided and translates them literally to read:

Eine Steuerrückerstattung kann erfolgen, wenn der Reisende Waren, die außerhalb der EU ausgeführt werden, spätestens am letzten Tag des dritten Monats nach dem Monat, in dem der Kauf getätigt wurde, gekauft hat.

As in the source text, the goods are being purchased after having been purchased. Makes your head spin, doesn’t it? Could these issues have been avoided by putting everything in the active voice, for example, ‘You can claim a tax refund if…’? Maybe.

In any case, before you hand your text to the machine it makes sense to:

- determine whether, if at all, you need passive verb phrases;

- turn them into active phrases to ensure that the person doing the action is clear;

- avoid errors which will be translated literally.

Easier said than done? Well, it’s usually not too difficult. And it’s worth it. Next time, I’ll tell you about how leaving out seemingly insignificant commas will make the machine change the meaning of your text completely. Lots of fun to come!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed