#8 Semantics, spelling and vocabulary: creating a new kind of ambiguity?

Hi again, and welcome to part 8 of the series on machine translation and plain English. Let’s look at some “lazy solutions” for simple problems.

Do you know what the English word “snap” means? It can be a verb or a noun and it can have several meanings. It’s what linguists call a homonym, a word that has the same form (and sound) as another word with a different meaning. In the following sentence the word “snap” refers to the audible cracking sound the component part makes when it is slid into place:

You will hear a firm snap when the earcup cushion is properly in place.

In German the word would be “Klicken”. In the given context (in connection with the verb “hear”) the word “Einrasten” (also “Einschnappen”) is acceptable, as one free online translation program suggests:

Sie hören ein festes Einrasten, wenn das Hörmuschelpolster richtig sitzt.

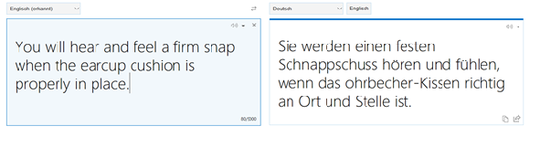

(Note: „Polster“ is the Austrian German word for German „Kissen“.) Another program, however, suggested this:

“Schnappschuss” is the sense of the word snap used when talking about photography: taking a snapshot. So, this is a case of the computer offering the wrong sense for homonyms in context. Not what I call helpful.

We looked at a similar situation in an earlier post. Remember the “match head” flickering? The computer thought that “match” referred to a game and translated it to the German word “Spiel”:

The flame on the match head danced and jumped in her fingers…

Die Flamme auf dem Spiel Kopf tanzte und sprang in den Fingern…

This is a very obvious example, and there many are other cases where it’s not immediately apparent that the semantics have changed:

On your initial visit to the chiropractor, he or she will take a thorough case history and give you a full physical examination. Your blood pressure may be tested and blood or urine specimens sent for analysis. The practitioner will frequently feel the spinal column to reveal where movement is restricted or excessive, as well as possibly testing mobility in other joints. X-rays are taken, if necessary.

In this example the reader is being told what to expect from the visit and the examination. The machine translated the underlined sentence as:

…Der Behandler wird häufig spüren, dass die Wirbelsäule anzeigt, wo die Bewegung eingeschränkt oder übermäßig ist, sowie möglicherweise die Beweglichkeit in anderen Gelenken testen. Röntgenstrahlen werden, wenn nötig, genommen.

This conveys the “perceive by touch” meaning of „feel“, rather than the “examine or search by touch” meaning intended and indicated by the immediate sentence context, the co-text. If the machine had read the context correctly, it would not have made this error. Nor would it have produced the rather confusing (and co-referentially faulty) version of the following sentence, where “should look at it” is rendered as “darauf achten” (take care that…, make sure that…) and the translation of “it” in “If it does fail” does not refer to the mower but to the manufacturing and testing:

The mower has been carefully manufactured and tested. If it does fail, an authorised customer service agent for our products should look at it.

Der Rasenmäher wurde sorgfältig hergestellt und getestet. Sollte dies fehlschlagen, sollte ein autorisierter Kundendienstmitarbeiter für unsere Produkte darauf achten.

Readers (and human translators) rely on the context to help them understand the meaning of a text. Machines do, too, but sometimes they get side-tracked by unfamiliar constructions or constellations and come up with sentences like this one:

Bent under hoods of raincoats or with plastic bags on his head, some with blankets over his shoulders or over his heads, some carried bags, others pulled suitcases, the windscreen wipers beat rhythmically back and forth, like hands who wanted to blur the picture, wiping away, he heard the navigation device: “Please turn around if possible!”.

Confused? (And no, it’s not science fiction. The text is not about people with more than one head! It describes a group of refugees as seen by the driver in the car and should read “…on their heads” etc.) Luckily, if you know German, you would notice this kind of error quite quickly. The situation is slightly different for the following example:

Sind die Daten für die Erfüllung vertraglicher oder gesetzlicher Pflichten nicht mehr erforderlich, werden diese regelmäßig gelöscht.

If the data are no longer required for the fulfilment of contractual or statutory obligations, they are regularly updated.

If your data are being “gelöscht”, they are being deleted. Updating may include deleting, but I do think that there is a difference between these two actions, and seen from a legal perspective, this could certainly be an issue.

Let’s briefly look at misspellings. Typos. Letters switching position. A wrong spelling or the autofill on overdrive. They happen, don’t they? And they’re not really an issue if your translator is a human being. But what would happen if you were to enter sentences like the following into a free online translation program?

Despite his looks, the man had an aurora of calmness and competence about him.

He couldn’t help his eyes wondering up her shapely legs.

Can you guess? What do you think?

See you next time!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed