What’s the difference between Esperanto and Klingon?

From a broad perspective, the answer is next to nothing. Both are constructed languages spoken by a limited section of society, the only real thing setting the two apart is that Klingon was designed for a fictional world then made the leap to real-world speakers while Esperanto was initially designed for real-world use.

Of course, each has its own unique grammar and vocabulary, as do all constructed languages or conlangs.

While researching conlangs for this article, I found a quote from Joanna Russ’ 1970 novel And Chaos Died in a Believer Mag essay:

“There is nothing like an arbitrary set of symbols to fix the operations of the mind”

Indeed, for conlangers around the world, crafting languages is both an intellectual and cathartic pursuit, one that some enthusiasts dedicated decades of their time to.

Auxlangs and artlangs

Some conlangers focus on auxlangs: languages that are intended to bridge the gaps between existent natural languages and facilitate greater international communication, Esperanto, arguably the best-known conlang with an estimated one to two million speakers, falls into this category.

Other conlangers turn their attention to artlangs: constructed languages that prioritise aesthetics over the language’s potential for cross-linguistic communications. Here, the focus is not just on sublime phonetic sound patterning though, it’s equally about designing logical and functional systems for morphemes, lexemes, and syntax that work in context.

For many artlangers, the point is to create something that cuts through the messiness of natural language.

Crafting perfection

Natural languages evolve slowly via unplanned processes that leave a lot of room for quirks and irregular rules, such as English’s silent ‘k’ — a remnant from the pronunciation of ye old times. Or indeed, ye, which we now pronounce with the ‘y’ sound but was once þ, the now non-existent thorn. So ‘þe’ was just an early way of writing ‘the’ (you can thank 20th-century advertising for both ‘ye’ and ‘olde’ by the way).

As human and computer language conlanger Chris Palmer told the journalist, Annalee Newitz:

“I like a language with a relatively conservative phonology and which does a good job managing ambiguity. You want enough ambiguity to have poetry and jokes and expressivity. But there’s a lot of needless confusing stuff in English—so I like a grammar that maximizes the good of ambiguity and minimizes the bad.”

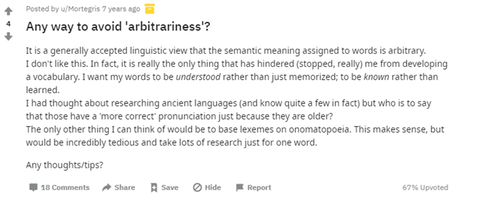

As you can imagine, designing a language is exceptionally hard work, and there are plenty of pesky annoyances in the way, including arbitrariness:

Making the leap to something akin to mainstream

Conlangs are not new inventions, they’ve been around for some time. Many scholars believe that the Lingua Ignota (the Hidden Language), which was first recorded in the 12th century by the nun Hildegard von Bingen, is the first engineered language.

And in the 17th century, there was a fad for “philosophical languages”, the influential philosopher John Locke argued for the removal of epistemology and ontology from language and Royal Society Members agreed with Dalgarno, Ward, and Wilkins positing languages of their own.

Tolkien, of Lord of the Rings fame, invented around 15 conlangs between 1910 and 1973, some including Quenya or High Elvish, are more formed than others but the philologist and author never fully formed any of his creations.

Esperanto itself has been around since 1887, alongside several other practical constructed languages.

While a niche pursuit, conlanging gained a greater community in line with technological advancements, the internet allowed conlangers from various nations to converge and share notes and ideas with one another. The Conlang Listserv was an early forum that has since been supplemented with numerous other spaces for enthusiasts to virtually convene, including The Language Creation Society and Reddit.

Accordingly, the term conlang itself remains relatively niche, although it gained more prominence after the linguist David J. Peterson won a contest by the creators of Game of Thrones, who invited submissions for invented languages on the Creation Society’s pages in 2009. Peterson’s 180-page Dothraki entry won, and by 2013, Game of Thrones’ popularity had skyrocketed.

In line with this, other shows in the making and television networks became increasingly interested in having their own conlangs. According to The Atlantic, by 2016 Peterson was working full-time in language creation. For most other conlangers though, the crafting of languages remains a passion project.

Whose language is it?

One has to wonder what happens to conlangs once they are released into the wild. Do their creators get upset when language users modify the creation to suit the real-life needs of speakers, does this highlight issues in the language that the authors failed to spot?

Johann Martin Schleyer, a German Catholic priest created Volapük in the 19th century and at one point, it had 280 clubs worldwide and more active speakers than Esperanto. The language didn’t last and neither did its popularity because Schleyer got rather upset when other speakers tried to introduce neologisms.

A labour of love to what end, we might ask ourselves. Perhaps the goal of any conlang is the beauty of the construction process itself, a unique glimpse into a “set of symbols to fix the operations of the mind.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed